The neuroradiology subspecialty exam (aka the CAQ or certificate of added qualification) is a tedious, basically redundant, and expensive waste of time taken by a relatively small number of people every year.

As a result, there are very few dedicated recourses.

In fact, there is only one, and it’s Sulcus.

Based on an informal survey I did of CAQ takers, the Sulcus bank is relatively popular despite what are generally poor reviews online. In my informal poll, almost half of respondents admitted to using it. I chalk this up to the CAQ exam being exceedingly expensive, people not wanting to fail it, and this being the only dedicated product.

Related note: Sulcus also now offers MSK and Mammography programs, neither of which I looked at.

Reviewer Disclosure

Sulcus did not pay for this review nor have they seen it prior to publication.

They did provide me with 7 days of free access. I have a life, so that wasn’t sufficient for me to view the entire product, but it was enough for me to form an opinion. I’m not sure I would have finished it regardless, and I did not purchase the product afterward for further studying.

I also have no discount code for you, dear reader.

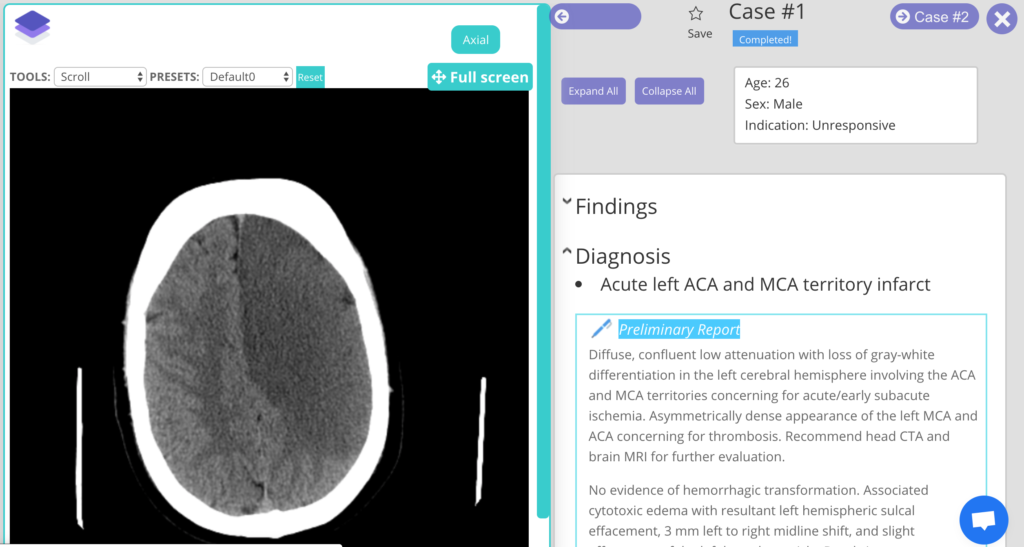

Platform

It’s a little clunky, but it works.

You must “create a quiz” as a separate step before you can actually take said quiz.

There is no tutor mode.

The site is technically mobile-friendly but the left sidebar (which is just the question numbers) takes priority, meaning that you need to scroll down past the question navigation to do every single question and read every explanation. Very tedious.

Content

There are a total of 562 questions grouped into 175 cases.

As in, there are several questions per case/diagnosis/image(s). For example, doing my first 5 cases used up 16 questions.

The cases themselves are solid. But when each case has three or sometimes four questions, the first is usually high yield, the second is borderline, and the third is basically just for giggles.

The question format is nothing like CAQ. Most CAQ questions are diagnosis-based.

Many Sulcus questions are multiple-choice “pick the correct statement” nonsense, where you evaluate a bunch of statements and then pick the one that is true. It also contains questions that are negatively framed (“which of these are NOT…”) questions that are garbage psychometrically (in their defense, these still crop on ABR’s exams rarely as well).

You’ll also get a lot of extended multiple T/F questions, where you need to evaluate a whole bunch of statements about the diagnosis and get each of them right in order to be “correct” overall. So, the end result–as other reviewers have alluded to–is mostly irritating/demoralizing.

Extended matching questions are pretty rare but fine.

Overall, the bank trends too much toward hyper-detailed in-the-weeds stuff, making it very inefficient to review in quantity for a busy practicing radiologist. The CAQ is an image-based test mostly of diagnosis, so testing a whole bunch of second-order factoids is not worth your time.

In Sulcus’ defense, I have a suspicion that the CAQ exam has changed significantly over the years. It very well may be that its current format more closely resembled the CAQ of old before changes brought the question style more in line with the modern multiple choice offerings of the Core and Certifying Exams. I support this theory with two points.

- No one would choose to write questions like this for no reason.

- The current (but clearly out of date) CAQ exam study guide from 2017 suggests that most questions would be part of linked question sets: “After the candidate makes her/his choice, one to three follow-up questions will typically be asked.” This is simply not the case. Most questions are solitary single best answer and do not go on to hammer you on miscellaneous second-order details.

Survey Results

I did a brief survey online and got 38 responses. Of the 18 people who said they used Sulcus, there were only two written comments: “didn’t think was relevant” and “was the highest yield by far.”

I think the reality is somewhere in between.

Pricing

$399.

Free Sample

There is one sample case in a slideshow at the bottom of the main page.

Verdict

Eh, pass.

A decent collection of wide-ranging cases; not a bad learning tool but extremely expensive related to other options and not an efficient CAQ review for the practicing neuroradiologist.

Unless you really have a CME fund to burn and nothing else to spend it on, you don’t need something this tedious and demoralizing to get through for the purposes of passing the CAQ exam. Some regular cases books, like Neuroradiology: A Core Review, will get the job done.

If you really just want a chance to see some pretty solid cases, take some great and some excruciating multiple-choice questions, and really hammer some low-yield esoterica to impress trainees and specialists, then this is an excellent choice.