If you have ever dabbled in personal productivity or internet software, you may have heard of—or already be using—Notion.

Notion is an incredibly powerful and sometimes complicated web software that allows you to create, essentially, a digital brain/personal database for just about anything.

Many companies use Notion for literally everything, and there are certainly many powerful features (some you can pay to unlock), but the personal version of Notion is free and incredibly powerful (and is what I use).

One of its key features is that it allows you to easily create and update databases—think flexible, easy-to-use Excel spreadsheets on the fly—including all different kinds of complicated fields like file attachments and tags that can then be searched and filtered accordingly.

I have multiple workspaces in my Notion for multiple reasons, including everything I keep track of to run Independent Radiology, but one use case I was also able to get my wife (who smartly does not share my obsession with digital tools) to implement was Notion to organize her CME.

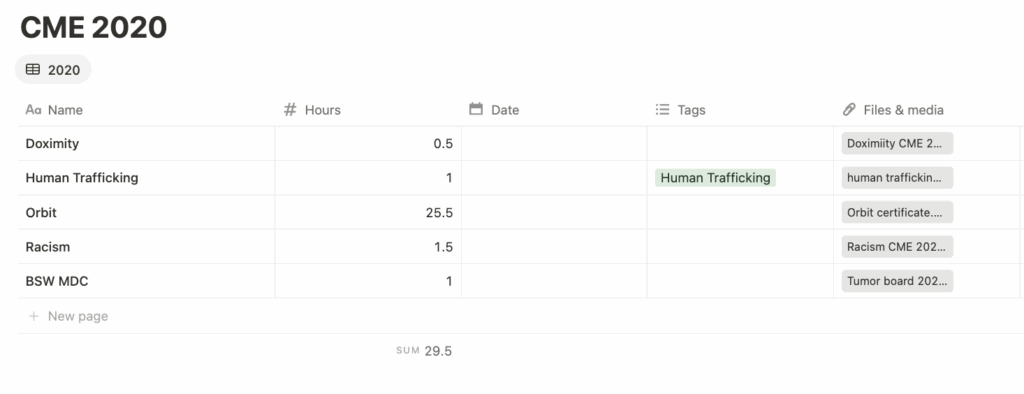

This is the very simple way I have my CME tracking set up:

A simple table that allows me to easily enter the name, hours, and tag (opiates, ethics, etc) for every CME item I complete—and then attach or upload the corresponding certificate so the proof is never lost. Adding more columns like date done or granting organization would be just a simple click. I make a new table every year.

Because Notion is on the web and is a well-funded, stable platform, this means I can add or find any element at any time whenever I need it—and retrieve it easily if I ever get audited by the Texas Medical Board, the American Board of Radiology, the hospital, or anybody else.

I have everything I need in one place to prove my compliance—and the pics to prove it.

If you’re keeping your CME in a physical folder, or in a folder on your desktop, or just letting them accumulate in your email inbox and hoping you’ll be able to find them in the event of an audit, I would consider trying Notion as an easy way to organize this—and potentially other parts of your life. I find it to be an easier way to stay organized than a thousand Google docs & sheets.

(Alternatively, the easiest thing you could do is just use OrbitCME (reviewed here back in the day, $20 discount affiliate link thingie here). It’s a webservice with a browser plugin that will give you credit for using sites like Radiopaedia, PubMed, or UptoDate, which means you can easily get all your CME hours taken care of passively just by doing what you’re already doing. You can upload your external CME events to it and keep everything in one place. Pricier but undeniably super convenient.)