This post is adapted from a response to a reader email. There’s a special kind of question I get a lot of every spring. The format is always the same: there is an unmet goal or stagnated improvement on a qbank during dedicated board review with a subsequent ton of anxiety about succeeding on the test. This is a common, frustrating, and scary situation for lots of students. The fact is that not everyone will meet their goals, but that doesn’t mean that you shouldn’t optimize your attitude and approach. It deserves as much if not more attention than picking your resources or schedule (things that people have no problem agonizing over ad nauseum).

You need to start by not beating yourself up. Your specific goal—whatever it is—is awesome, and I hope you get it, but you need to know that goals are only helpful as a means of motivation—not something to tie your entire self-worth into. A misconstrued or stringent goal can be demoralizing and thus does not serve you well. A friend’s stated performance, posts on SDN—absolutely none of that matters to your personal needs.

Don’t let demoralization prevent you from utilizing practice questions as a primary component of your preparation. The reason UWorld and other qbanks are good tools is twofold. 1) Your knowledge is only helpful if it helps you answer a question. The best way to see how to apply your knowledge to a question is with a question. 2) The explanation teaches you both the correct facts, the ancillary facts (incorrect choices), and the context/test-taking/pearls/trends/etc.

Stop and consider why you feel sad when you review your performance after finishing a qbank section. Because being optimistic and believing in your strategy are important components of getting through this tough period and gaining/maintaining your momentum.

A lot of people shortchange themselves on point #2. They get upset when they get a question wrong and don’t use it as a learning opportunity. You should almost want to get questions wrong, because then it means you have an opportunity to improve, a potential blind spot to weed out. There are lots of reasons to get questions wrong and you need to approach the explanations as a chance to learn, not a chance to be disappointed. When you get questions wrong, flag them and do them again.

The other thing students do is use that negative emotional valence to overread the explanation. They take an exception and turn into a new rule. They try to generalize too much. They take something specific to one question and apply it to other questions where it doesn’t apply (“but last time I guessed X and it was Y; this time it’s X, wtf!”). All of this comes from stress and self-doubt.

The way to not burn out is to try to actively switch your attitude from fear to excitement. You’re doing this so you can learn, and, in a few weeks, you’ll be done. That is astoundingly exciting. It’s a huge milestone. When you start feeling amped up and nervous, you need to say “I am excited.” Excitement and panic are both states of heightened arousal, and they’re more similar than you’d think. Whenever you feel the panic rising, whether after a section on the qbank or the real thing, don’t “forget” that you’re actually excited.

If you don’t have much trouble with time management, I’d continue using tutor mode for the vast majority of your dedicated studying. Remember, the qbank is primarily about learning first and emulating the test day experience second. Stop paying attention to how you’re doing as you go through a section. Whether you do bad or good or your score changes doesn’t matter. This is how you’re going to study and you’re going to embrace it. Use books to supplement as needed when an explanation isn’t enough, need another perspective, or you hit something that requires re-memorizing a table (cytokines, glycogen storage diseases, things of that nature). You can switch to timed blocks to simulate the exam the last week and get into a groove. Find the confidence to go with your gut, not agonize, not get stressed by a long question stem, etc. If one particular thing seems like you’ll never learn it, then don’t. Your score doesn’t hinge on a single topic. For most people, there’s plenty of other material to learn instead.

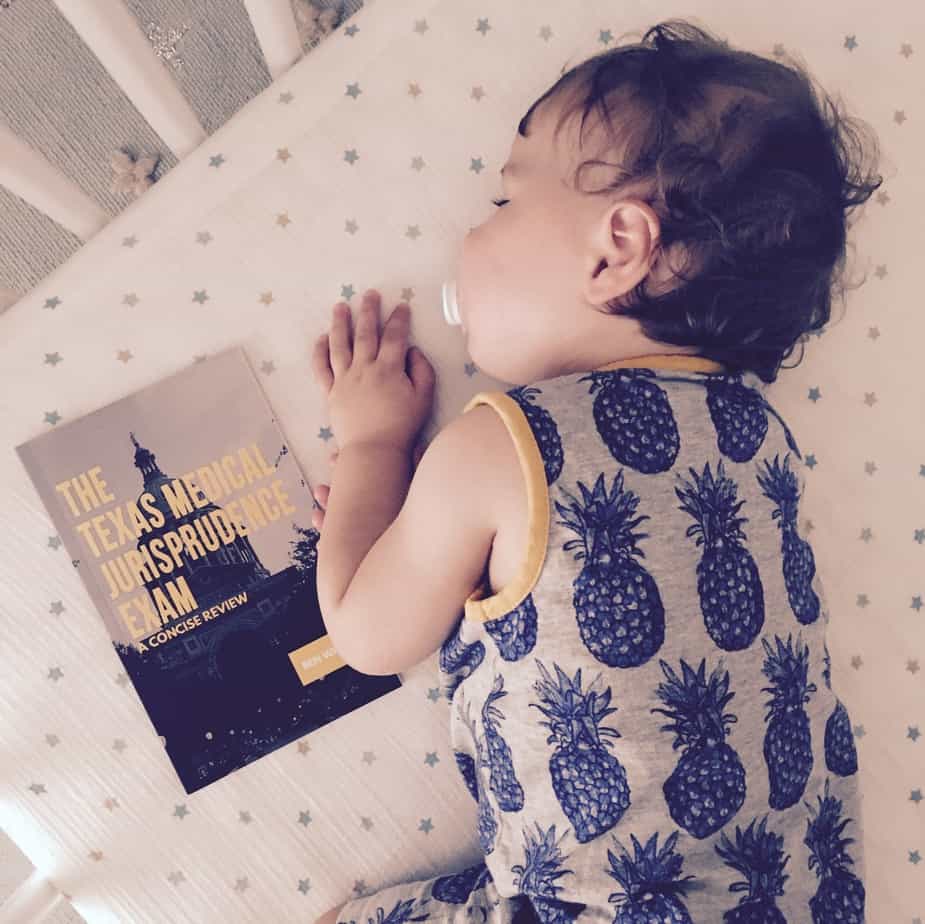

Don’t forget that Step 1 should be a happy time. It’s the culmination of another chapter of your life and marks the transition from seemingly endless book learning to finally starting your journey in clinical medicine.

You need to study, do your best, and be proud of yourself.