The CAQ exams are likely the least discussed and widely known facet of radiology certification. Until now.

Background

The CAQ—or, Certificate of Added Qualification—is something most radiology residents and other doctors don’t even know about. It’s an extra subspecialty certification you get by giving the American Board of Radiology (ABR) a bunch of money and taking an extra subspecialty exam so that you can say you did it. Some radiologists then put their CAQ-holding status at the bottom of their reports (“This study was interpreted by a CAQ Neuroradiologist” or equivalent) under the pretense that the CAQ confers authority and quality to their work (as opposed to those things coming from actually being thoughtful and good). You see, many radiology fellowships are actually not accredited by the ACGME, and most subspecialized radiologists have no magical exam they can take for true bragging rights. You can do an MSK fellowship, and you can say you are a fellowship-trained subspecialized musculoskeletal radiologist—but you don’t have a CAQ as a proxy for “subspecialty expertise.”

Historically, CAQs have only been available for neuroradiology, pediatrics, IR (which now has its own boards/residency), and nuclear medicine (which also has a separate board, the ABNM). In practice, neuroradiology is the most popular CAQ. In 2019, 198 examinees sat for it. Compare that with 59 for pediatrics. Nuclear medicine? 4.

Many practicing neuroradiologists have never taken the CAQ exam and do not hold the certificate. Some jobs (especially in academics) demand it. It’s also important as an extra credential for expert witness work (if that’s something you’re interested in). Many clinicians may want a subspecialized neuroradiologist, but the majority have no idea the CAQ itself exists.

For years, the CAQ was another exam you had to fly across the country for. This was especially galling in recent years because it’s just a half-day exam, and—with the advent of the choose your own adventure style of the Certifying Exam—largely an expensive and duplicative waste of time.

Registration & Fees

To officially learn more about the CAQ, see the ABR’s handy page titled neuroradiology.

In order to register, you generally must have completed a 1-year ACGME-accredited fellowship and been in practice for one year (or completed a second year of fellowship) with at least one-third of your time dedicated to neuroradiology. So yes, you can still practice as a general radiologist and sit for the CAQ.

When you register, you will need to provide—in addition to a sack of cash—a diploma from your fellowship and a letter from your service chief or department chair acknowledging that you’ve been in practice long enough and have been doing enough neuroradiology.

Registration is open only from February 1 through April 30. This is because confirming your eligibility is an apparently arduous task and cannot be stomached year-round.

I actually meant to register in 2019 but missed the window. When I tried to see if I could still take it anyway, I was told via email: “The time span from the close of the application window is required to process and approve/decline applications based on training – for which the process is thorough and time intensive.”

What is this process? They check your diploma and letter. Ironically, despite the form being very short and this process being both thorough and time-intensive, they didn’t notice my letter (you do get a copy of your application emailed to you, and it was sitting right there), so I had to re-send it. The ABR person acknowledged it momentarily, and I was then magically approved to send in more money.

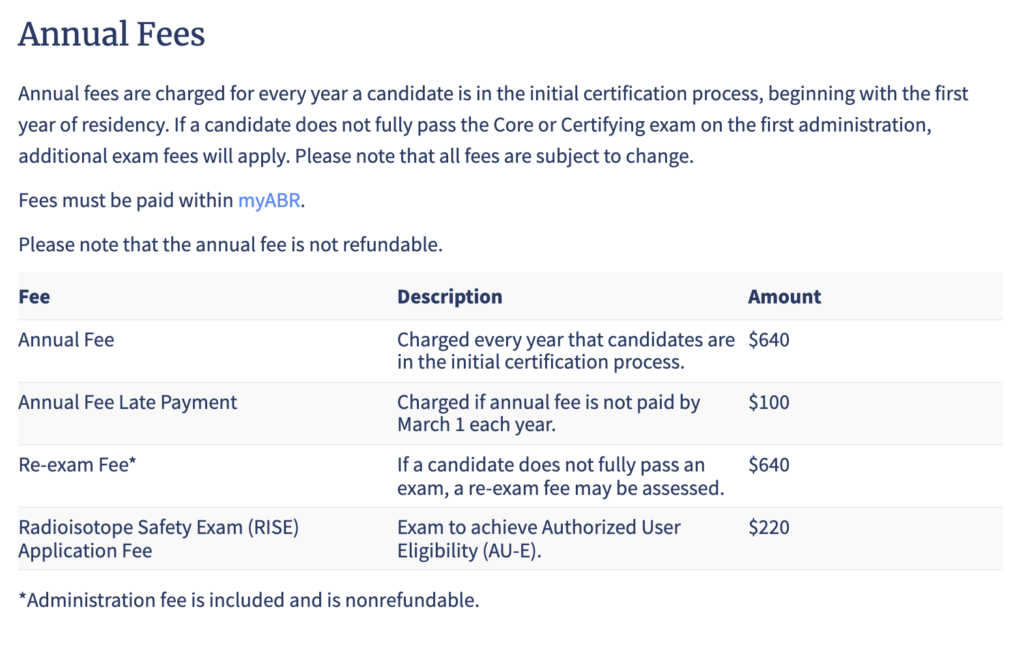

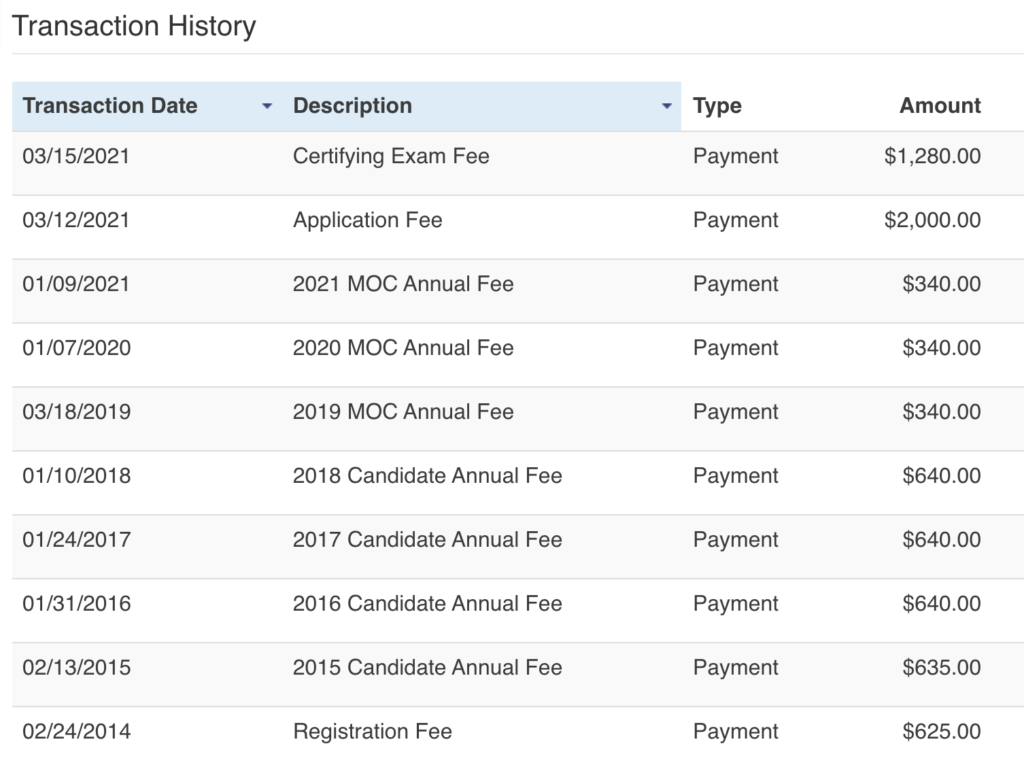

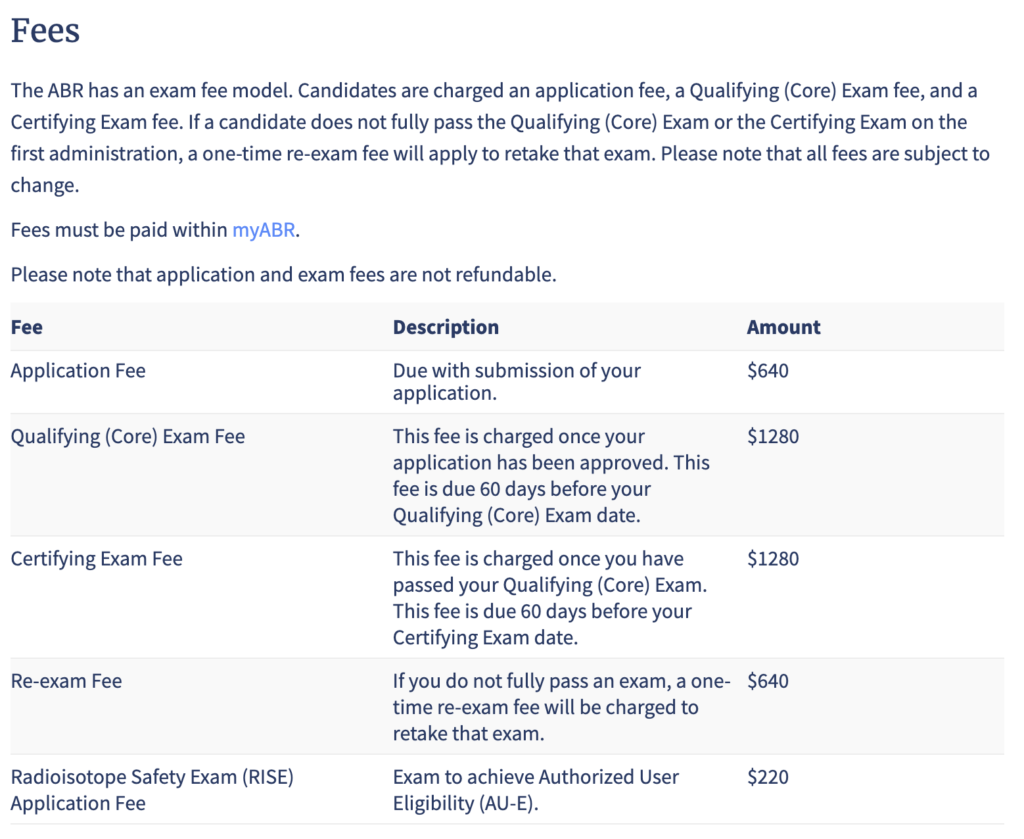

In 2020, the fees were $1635 to apply and another $1635 to register for a total of $3,270.

As of September 2021, the exam fees have dropped.

You now spend $640 as an application fee and then later a separate $1280 exam fee for a total of $1,920. You’ll spend another $640 if you fail and need to take it again.

Format

The testing format and software are identical to the ABR’s other computer-based offerings like the Core and Certifying exams with an image-rich gauntlet made up of predominately “single best answer” format (and typically “what is the diagnosis?” style) questions.

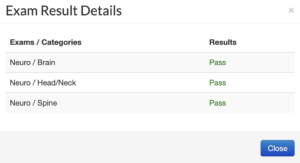

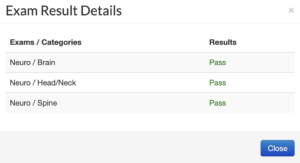

The exam is composed of 180 questions in equal parts from the categories of Brain, Spine, and Head & Neck. Unlike the current iteration of the Core Exam, you can condition an individual section and be forced to re-take just that section (at least you won’t have to travel for an hour-long experience). If you condition two sections, you simply fail the test.

You have 3 hours 15 minutes allotted for the questions, 20 minutes of break time, and 20 minutes for the tutorial for a total maximum experience of 4 hours 5 minutes.

Between 2013-2019, between 158-232 examinees have taken the exam annually with a passing rate between 79-95% (mean 86%) and a condition rate between 4-12%.

My Experience & Results

On exam day, I got a brief connection lost warning twice, lasting for a few seconds before being reestablished, otherwise no interruptions. For more discussion of the ABR’s online platform, please see this post: The ABR Online Testing Experience.

Despite the fact that many review resources like to show you multiple questions based on a single image (and the official guide discussing it as I describe in the next section), the vast majority of questions are “What is the diagnosis?” questions. This can lead to some frustration, as in real life, many things (e.g. many spinal tumors) are straight differential cases that you would never come down hard on, and a couple of blurry MR images from the 80s aren’t how anyone is used to reviewing cases in real life.

The easy parts of the exam are similar to the OLA MOC questions, and the harder parts, are, well, harder. The best preparation strategy is to make sure you can get all the easy questions right, leaving yourself room to guess like everyone else when they show you some blown-up spine or a pediatric case you haven’t seen or thought about since you prepared for the Core Exam.

It took me two hours forty minutes including breaks. With the online format, you can take a break whenever you want, but all previously seen questions will be locked and cannot be altered. You can take more than 20 minutes break but exam time will continue to count down during any additional breaks.

The ABR states results are released in 4-6 weeks. In 2021, it was exactly four weeks to the day.

Like the Certifying Exam but unlike the Core Exam, there is no granular data. You either pass or you don’t.

Preparation

As always, the ABR releases a study guide. The current version hasn’t changed since 2017 and is mostly useless: it is a list of all topics in neuroradiology. It does include a few practice questions at the end.

It also seems to be out of date. The guide states that there are 60 individual questions with 180 total items, suggesting that the average case has three questions and that are a lot of second-order questions. Indeed, it states: “The case mix will reflect the typical clinical practice of a neuroradiologist. Thus the majority of the cases will be examples of relatively common entities but the follow-up questions will require a greater depth of knowledge than that expected of a general radiologist.”

This is simply not the case. Like all modern era ABR radiology exams, most questions are standalone diagnosis questions and relatively few are multipart deep dives.

As you might expect, your daily experience as a likely almost entirely adult radiologist does not prepare you very well for peds-type questions or even probably most testable spine pathology, so I encourage you to spend at least a few hours refreshing that material.

Qbanks

A relatively popular but generally not well-reviewed resource is Sulcus, the only neuroradiology-specific question bank. I reviewed it here and think you can skip it.

Board Vitals‘ Certifying Exam Qbank has 179 neuro questions, and 30/82 peds questions are peds neuro (10% off with code BW10). BV has a decent mobile app where you can even download questions for offline viewing and now finally saves your preference for the “show exhibits” toggle in the app, so you only have to hit it once to show the images automatically for all questions. While there is no image manipulation, it’s not necessary in this setting, and you have the choice between untimed vs timed and tutor mode vs test mode.

A practicing neurorad could get through the questions in a few hours, and they are overall easy (you should get most correct without issue), but for the purposes of rapidly getting you in the question-taking mindset, it’s not a bad experience. Then again, you may feel that OLA is enough. Overall, the BV experience is much more pleasant than Sulcus, even though the learning opportunities are lower. It’s definitely a floor, not a ceiling.

There are some negatively framed questions, which I want to say is unacceptable, but the fact is the ABR still hasn’t fully purged them from their tests either. There’s some image reuse for multiple questions, which is a bit lame, as well the habit of asking “which statements about this entity are true” style of question, which isn’t how most ABR questions are formulated these days. Some good high-yield anatomy but giveaway easy for a trained neurorad. I got 90% correct in my warp-speed review; of the ones I missed, I would say 1/2 were straight-up bad questions: a couple were due to bad images (which in fairness the ABR loves to do), and the others had psychometrically bad answer choices on the “which of the following are true” type questions.

Because the peds neuro questions are randomly found within the peds section, I’d recommend doing those on tutor mode so you can just skip the majority. These were super classic diagnoses but may help bring some comfort. I didn’t get any of them wrong but are nice to see since most people don’t do much peds.

Not a great value for the 1-2 days you’d actually use it but cheaper than Sulcus. I think you can probably skip both unless you really want to see more questions.

Case Books

I think good old case books (e.g. RadCases, Case Review Series) are by far the most cost-effective way to prepare.

In my very brief survey, the best collection and value of high-yield low-pain processes and reasonable second-order factoids is Neuroradiology: A Core Review. It includes some high-yield peds and is organized by general theme. The ebook version you unlock with the code inside the cover is essentially a multiple-choice quesiton bank, and each chapter has 34-40 questions grouped into a smaller number of cases (diagnosis question often followed by 1-2 additional fact questions concerning pathogenesis, prognosis, management, etc). A practicing neurorad should probably get almost every diagnosis correct and miss a second-order factoid here and there, which means that it’s probably not a bad resource to use. If you blaze through and know it all, then I think you’re in pretty good shape.

Note that anatomy is not meaningfully covered, so it would still behoove you to make sure you have your gyral and functional anatomy, skull base foramina, cranial nerves, midline sagittal anatomy, head/neck spaces/levels/structures down pat.

While there are a couple of duds, overall the questions demonstrate broad depth, good examples, and some honestly refreshingly well-written explanations. It’s an excellent book. I’m not ashamed to admit I learned some facts that I didn’t know previously or had forgotten, including some fun ones to pimp my residents on and shore up my knowledge of vaguely useful esoterica.

The phone app for the online version is a little buggy, and the images load as thumbnails whether you’re on your phone or just using the full website. You can slam through the book in a dedicated evening at the bare minimum.

If you do more than one case book, you’re going to see a lot of overlap.

Survey Results

I did an informal online survey and got 38 responses. The overall pass rate of the respondents was 86.8%, which is right at the ABR average. Everyone had passed the Core/Certifying exams on their first attempt.

55% had to take the CAQ for their job, and 74% had completed a 1-year fellowship.

How long did people study (and by study I mean an hour or more somewhat consistently)?

- 5 weeks or more – 15.9%

- 4 weeks – 39.4%

- 3 weeks – 18.4%

- 2 weeks – 10.5%

- 1 week – 7.9%

- < 1 week – 7.9%

Of the 5 reported failures, 2 studied for 1 week, 1 for 3 weeks, and 2 for 4 weeks. Not much help there.

I personally studied somewhere around a few hours total looking at Sulcus and BoardVitals during the weeks leading up to the exam and then blazed through A Core Review the night before. So overall less than 1 week, but I think I would have felt better with a full week, maybe two.

I suspect that for most people doing 75%+ neuroradiology—especially if that involves some high-end stuff and not just strokes/hemorrhage/fractures from the ED and degenerative spines from the community—that a week or two is probably fine, but it would seem that over 50% of takers are spending a month or longer with some degree of consistent study.

Only one person who failed remembered and shared their qbank performance: Sulcus: 56%, BoardVitals 76%, and RadPrimer 70%. I’m going to guess you probably want to be at 80%+ on non-Sulcus products, and probably at least 65% if not 70%+ on Sulcus.

I would also guess that if you had borderline performance on the Core Exam, you probably want to put some serious hours in. If you destroyed the Core Exam without a sweat, this will likely be a breeze.

Unfortunately, as with all ABR exams, we simply don’t have the data to meaningfully predict performance.

Conclusion

The CAQ is lame.

It’s expensive, and should absolutely 100% be folded into the Certifying Exam, which can also coincidentally include 180 neuroradiology questions.

There are no particularly good dedicated resources. Sulcus is probably too expensive, too hard, and too demoralizing. While casebooks are generally geared toward the Core Exam, the fact is that they provide a good knowledge floor and will remind you of what should be low-hanging fruit on topics you don’t see often in daily practice.

As with all ABR exams, be prepared to be irritated.

Yes, I did roll over my attending chair, the

Yes, I did roll over my attending chair, the