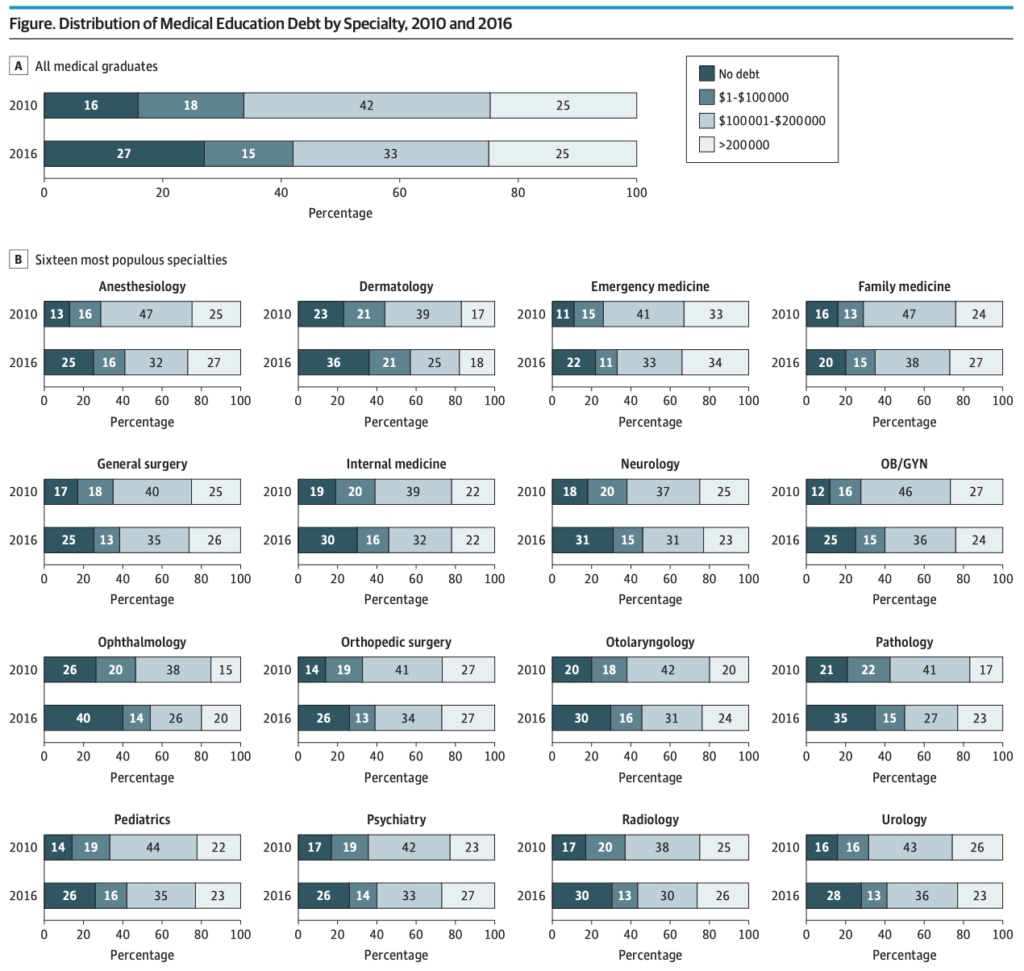

A handful of notable free tuition experiments aside, the combination of rising medical school costs, vocational pressures, life-quality issues, and reimbursement battles has clearly had a chilling effect on many lower-paying specialties and continues to funnel medical students into procedural fields and surgical subspecialties.

An individual student’s personal calculus aside, the broader question is still worth answering, particularly as doctor’s compensation is once again in the news:

Taking into account the whole picture including student loans, a delayed start in the workforce, and high hours—is medicine worth it?

Well, we’re not going to answer that question today.

But we are going to briefly discuss one of the financial downsides of becoming a practicing physician: residency. This is perhaps compounded even more now with the blurring “provider” divide, where midlevels like NPs are increasingly able to create a similar if not substantially broader practice to resident physicians while also being able to make adult financial progress (paying off loans, meaningfully saving for retirement) immediately after school (and can even change specialties with little friction!).

All of that is a massive, thorny issue. But for this short post, I’d just like to quickly share two interesting data points that vindicate all you residents out there frustrated with watching your loan balances balloon.

Funding is nice, but cheap labor is cheap labor

The first is from a (not new) paper by UC Berkeley’s Nicholas Roth titled “The Costs and Returns to Medical Education.” The paper looks at medical school and training as a combination of financial and opportunity costs and calculates the relative return for different fields (I discussed it at length here if you’re curious), but it has an interesting statistic toward the beginning.

After Congress passed the 1997 Balanced Budget Act, which capped government payments to hospitals for residents, hospitals added over 4,000 more residents than the government would support. This suggests that market forces are at work as hospitals try to hire residents until the marginal value of an additional resident is zero. It also suggests that hospitals profit from additional residents long after the point when our government stops funding resident education.

That’s fascinating because it dovetails perfectly with the narrative all residents believe that hospitals benefit from their cheap labor despite the ludicrous claims that it “costs more” to educate a trainee. (Right, because if that were the case, why ever hire a midlevel fresh out of school?)

The Residency Fire Sale

And if there was any further doubt, look no further than the recent Hahnemann bankruptcy fire sale for corroboration. When the hospital went under, they tried to sell their 570 residents slots as a tidy parcel to the highest bidder as if their residents were a commodity like office furniture. The winning bid was $55 million, meaning that even in an absurd market situation with a desperate seller, each resident was worth about $100k, not too far from what Medicare provides for each residency slot (again under the pretense that it costs about as much money extra to the institution to train a resident as they actually earn in salary).

Details Matter, But It’s Not Pretty

Of course, not all residents are created equal from a finance perspective. There are both intra-speciality and inter-specialty differences. While attending compensation is generally tied to the generated revenue, all residents of a given training level at an institution are paid the same amount. For an easy example, a radiology resident at a program that has 24/7 attending coverage provides much less bankable value than a resident who takes independent night call.

Of course, I see zero chance of this changing meaningfully in the near (or any?) future, but given the renewed political discussion of physician compensation and the growing role of non-physician providers, it’s worth pointing out that the reality on the ground (low trainee salaries, huge opportunity cost for additional training time) is a system construct that stakeholders should address when considering the future of medical training.

Parting Question

In the “non-profit” world of academic medicine, why do institutions need to profit from training doctors?