The first few months of radiology residency can be pretty bewildering. It’s rare in adult life to start from scratch quite as much as you do the summer you transition from internship. Even if you did some studying during internship or you were fortunate enough to have electives in radiology during your intern year, there is a steep learning curve in July, and no one’s foundation in radiology is typically all that strong in terms of actual working ability.

Even though you’ve been looking at things and talking your whole life, it isn’t the same thing as looking at medical imaging and dictating reports. And so the first few months are dedicated to learning the core skills of a radiology foundation: getting comfortable, learning the hospital and the EMR, understanding the radiologist’s roles in the clinical workflow, and putting up some serious imaging reps.

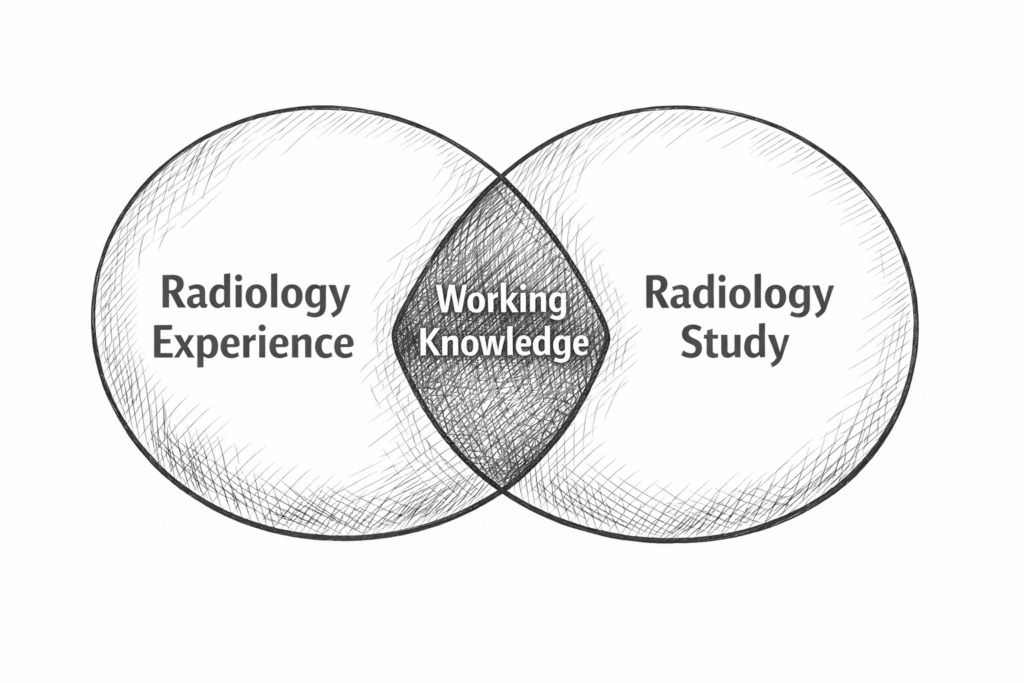

Junior residents will typically take some variety of call after a year, and—even if you don’t have independent call—I know that’s a big step. As your spirit attending, I do want you to continue seeing as many cases as you can and studying outside of work to make sure that you are rounding out your radiology knowledge to build on the things you’ve seen in real life and fill in the gaps for the things that you haven’t. The List Gods do not provide you with everything you need, and the Venn diagram circles of radiology experience and radiology testable knowledge from books/questions/videos/etc do not have perfect overlap.

The spring semester of the R1 year is a great chance to work on the deliberate practice of radiology. There is an iterative loop of interpreting radiology cases that we perform over and over again, and I find that most trainees struggle with certain parts more than others.

The Radiology Loop

I view the five-point interpretative loop as follows:

1. Attend

Bring your complete focus to every new case, because every case is a new patient who deserves your full attention and your best work.

2. Observe

Review the images to make the observations/findings. This involves scrutinizing everything, of course, but also involves practicing avoiding certain pitfalls, like missing findings at the top and bottom images or at the edge of the field of view, falling prey to satisfaction of search, and forgetting to do a targeted review of specific imaging areas to exclude relevant pathologies, second order findings, and seek pertinent negatives (the true search pattern).

3. Decide

Make the decision/diagnosis. This includes deciding if an observation is real or artifactual as well as settling on the differential or significance of a finding. Practice deciding to the best of your ability without perseverating on findings by endlessly scrolling back and forth or agonizing. Practice making a targeted review on the internet to help categorize a finding without getting too deep down the rabbit hole, and be willing to phone a friend or an attending to get an outsider’s more experienced perspective when you need it. Cultivating independence is critical, yes, but we can also get more reps and do more work if we don’t get too bogged down. Try to do it alone when you can, but don’t get trapped in your own head.

4. Describe

Dictate the report with the goal of an organized and concise but thorough findings section as well as a clear, actionable impression. I personally subscribe to the “the more you write, the less they read” perspective, but everything is truly a balance, and the goal is not for you to emulate any specific style but rather to figure out how you want to practice and how to do your best work.

5. Polish

Proofread and hone that report until it is as good as you can make it. I argue that sloppiness never stops at transcription errors or other seemingly less important things; it percolates and permeates. It’s important to practice doing your best work, and that may mean adjusting how you work so that you make great reports routinely.

More on Attention

Within the spectrum of giving each case your full attention, you need to set yourself up for success, and that means not cutting corners. That includes reviewing the history and utilizing relevant priors. Yes, it takes some more time upfront, but it also guides your search pattern and informs your decision-making. It is critical to the practice of radiology. And you will make so many fewer mistakes if you get into the practice of doing this consistently.

You would probably severely underestimate how many times I have seen people be wrong in their conclusion or agonize over a decision that didn’t even have to be made because they failed to look in the chart for relevant history, to look at prior scans and prior reports in your system, or even to see if there were prior radiology reports hiding in Epic available in Care Everywhere. There are countless age-indeterminate or nonspecific findings—including those that generate useless follow-up imaging and unnecessary admissions—that, with some scrutiny, are chronic or stable for years. You’re never going to bat a thousand on this kind of stuff, but you might as well try.

Additionally, those prior reports are often your greatest teacher. So please do not waste these opportunities.

Maximum Learning

Additionally, I strongly recommend that when reading follow-up scans, you take a moment to look at the presentation scan. In many cases, that initial scan when that stroke is less obvious or the pre-operative scan before a lesion is resected gives you the most valuable visual exposure instead of just monitoring a mostly stable ball of blood or resection cavity. Don’t rob yourself of the opportunity to see the full spectrum of radiology/pathology, and try to find things and see how they look and really evolve over time. These are an important part of your learning, so don’t waste them.

It is very reasonable to review your case first before looking at the priors and their reports so as to give yourself the opportunity to approach each case de novo. This is admirable if time-consuming, but don’t take the desire to bring fresh eyes to each experience as an excuse to cut corners and not review the priors.

Your Job

It’s your job, with the help of your attendings, to figure out:

- Where you are strong

- Where you are weak

- Which things you don’t like doing

It’s worth pointing out that the things you don’t like doing are often the things that you struggle with. There is a saying that practice makes permanent, so it’s important not to just try to get through the day but to really focus on these steps to build your skills and work on your tired moves:

If you don’t do things the thoughtful way on a regular day with no pressure, then you’re never going to do them well when you’re tired and under pressure. So we need to work on doing things the “right” (read: consistently improving) way every time, over and over again during the regular workday, to build up the muscles of doing radiology a better way.

And, those things we don’t enjoy aren’t as fixed as you might think if you’re able to cultivate a craftsman’s mentality.

There may be no universal right way to practice radiology, but there are definitely some wrong ones.

One Comment