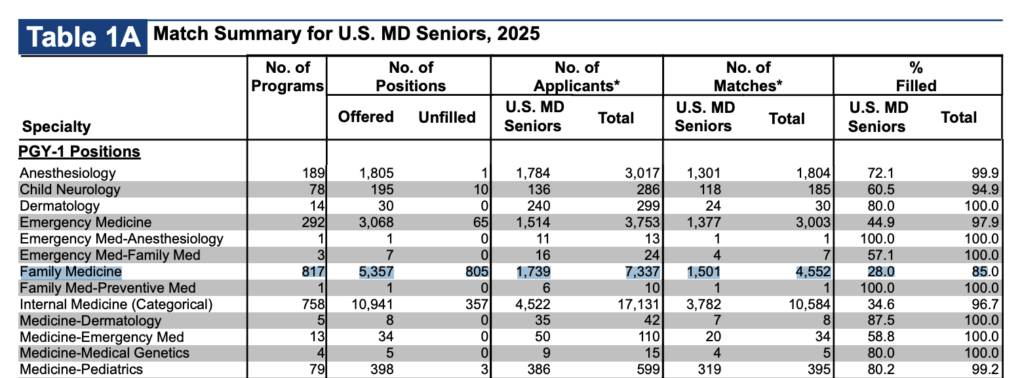

Another year of the NRMP match results, and Family Medicine continues to be a relentless slow-moving disaster within the house of medicine. 805 unfilled postions, only 28% filled by US MDs. Just 1,501 US MDs in the whole country matched to one of the most critical jobs in all of healthcare (1739 applied, but the discrepency is probably a reflection of FM being a back up option for several hundred people).

I think people see this and point out several obvious deficiencies:

- Pay

- Prestige/respect

- Midlevels

All true. All essentially impossible to easily fix within medicine and our training paradigms. Some people discuss the possiblity of special loan reimbursement, and that I suppose is obliquely helpful, but the reality is that PSLF already exists and there are already programs for working in underserved areas. Debt is a problem, but I don’t think tackling that head-on is going to solve the decline of primary care in the US.

Another suggested solution I often hear is to make family medicine sexier by allowing for different fellowships, creating more training options and allowing family docs to broaden their skills into things like dermatology.

There may be something to this, though I suspect in most cases, there probably isn’t. Even if such broadening were successful, it is probably counterproductive to the actual goals of primary care. A backdoor into dermatology is probably not going to solve a shortage of qualified practitioners. Nor do I think additional training is going to improve perceptions of prestige or respect.

The thing the ACGME can do to make things better are to change the training composition/requirements and especially length. Family Medicine should probably be a shorter, outpatient-focused course of training for general practitioners in the US.

In the era of massive midlevel expansion, it simply can’t be three years long. Anything else isn’t going to work to get people interested again.

In a world where many institutions struggle to attract aspiring family practitioners, I suspect the only solution is to fight fire with fire. I think we need more efficient training. We need to acknowledge that while more training is always good, it isn’t always necessary. And if we can’t get the job done in less time (though Canada is two years), then we need to seriously consider the efficiency of our process and the ability of our tools to assess competence.

We have, for too long, resorted to a proxy metric of time to tell us that somebody is skilled. This crude tool shouldn’t be the best we can hope for going forward. Nor will it help us address a possible post-AI world where physician retraining may become a more pressing concern.

So, I think the answer is just to start by shaving off a year and getting it done in two years.

(In a fantasy world, training duration would be as long as it needs to be. Strict training lengths are important to hospitals using residents for predictable labor, not because every doctor needs the exact same amount of training time to reach competency. The ebb and flow of patients in a resident clinic is probably slightly easier to accommodate than hospital service coverage.)

Given the current reality that many people in family medicine do not want to practice a significant amount of inpatient medicine, potentially refocusing a portion of that to an optional third year instead of making it a core part of the residency is likely one way to offer flexibility without fundamentally changing the field. Offering different paths for those who want to work in rural areas doing procedures and those who want to do OB are great ideas, but some serious introspection to figure out what the core of a PCP/GP should be in the US is overdue. I won’t claim to know the answer, but the match results tell us some stakeholders need to figure it out.

I also want to preempt anyone who wants to argue that doctors are already poorly trained and that shortening training will worsen that problem. The answer is, of course, all things being equal, that shorter training will be worse training. Many older physicians indeed believe that younger physicians are graduating “less well-trained” than previous generations. Part of that is a manifestation of reduced training volume. Part of it may be related to the increasing complexity of medicine. And part of it may be related to cultural shifts, such as decreased studying after work, and other such factors.

But that assumption also implies that there is no fat to trim, that all months of training are essentially equally useful, and that a shorter process should look the same as the longer process, just worse. All training is useful, but some is clearly necessary. The reality is that we cannot afford to ignore training quality. We need to provide better, more effective training. We need better measures. We need to reward hard work and variable skill so that the most competent people can graduate when they’re ready and not just when they’re older.

And ultimately, we need to rethink our fixation on time as the defining measure of competency. It’s not. It’s a crutch.

6 Comments

I’m no expert on med school curricula nor GME training but I have many years in family medicine and suspect your suggestions would do more harm than good.

Yes, by all means, dump most labor and delivery training and let the minority of those who want to deliver babies do a fellowship later.

But why shorten family med residency by a year and leave med school (which can cost up to $100,000/year) at four year for all physicians? Now that low cost federal loans are capped, a fourth year is a luxury most can’t afford.

Primary care is hard to do well and, while Canada gets by with two years, if I was going to compete with midlevels I’d want a third year with lots of office procedure training that offers value to future employers and patients.

Likewise, while few family docs need to know how to manage a DKA in the ICU anymore, some inpatient training so they know how to deal with that system as their sick and elderly patients go in and out of the hospital is valuable. Some of us also still moonlight as hospitalists when starting practices.

Finally, almost no students nor residents get any exposure to independent or DPC practices. If we ever hope to make primary care attractive again, letting them know about these options would be a step towards that.

I look forward to a guest post here from a primary care doc giving advice on how to improve neuroradiology training… ;-)

You may be right, though I think you’re straw-manning a bit here. To be clear, I’m not suggesting shortening residency would improve training, I’m saying shortening is probably needed to improve desirability of the primary care (if that is a goal the field holds).

Your point about the option of a third year that is guided by desired skill acquisition and not one size fits all is a great idea that I agree with. Not mutually exclusive (it’s in the post). That could be in an optional third year instead of an optional fourth year. My point here is that we could change the floor and probably immediately revitalize the field.

You’re right that medical school is also inefficient, but that is only obliquely relevant. I’m not making any argument about medical school length or quality or making the point that it should stay 4 years (I’ve actually also argued in the past that it should be 3). The issue there is that 1) med school changes can’t specifically benefit primary care and regardless 2) they are run by entirely different organizations. Trimming fat in one place doesn’t necessarily help the other, and no one entity controls the whole process.

To be clear, this post is not about the best way to train primary care doctors. I didn’t and won’t claim to know that. It’s a suggestion about dealing with a critical unpopularity that is jeopardizing the practice of primary care in this country, and, more broadly, my desire that we really develop competency-based and not time-based training paradigms (for everyone, yes, including neuroradiologists). I want great doctors; the time is just a crude proxy.

My med school (TTUHSC) has a program like what you’re describing. 4 years of med school and 3 years of FM residency is condensed into 6 years where effectively you begin FM residency during your 4th year. Big bonus of cutting out the 4th year of med school is you start making residency salary 1 year early and save on 1 year of tuition. https://www.ttuhsc.edu/medicine/admissions/fmat.aspx

That’s awesome, thanks for sharing. Probably something that should be studied for the broader country.

I think we can do it in 2 years like Canada. That’d be a good start.

Also I think a rebranding might do good. FM sounds too Hufflepuff-y or vanilla or plain, which in turn is a big negative for some or many people. Maybe something like GP, which is what FM is called in the UK and British Commonwealth nations? (I know GP means something different in our context, but that seems to be fading away with each generation, and besides there’s no good reason why we can’t co-opt it and reuse it for our own.) Regardless, just something that else would sound sexier than Family Medicine. And it’s wild how a simple name change or rebranding can change the minds of some or many people. For instance, that’s part of what George Orwell presumes in his “Politics and the English Language.”

My gut is that you’re right: “General practice” in two years is probably exactly the right noncontroversial goal and wordsmithing.

That would have been a much more succinct article.